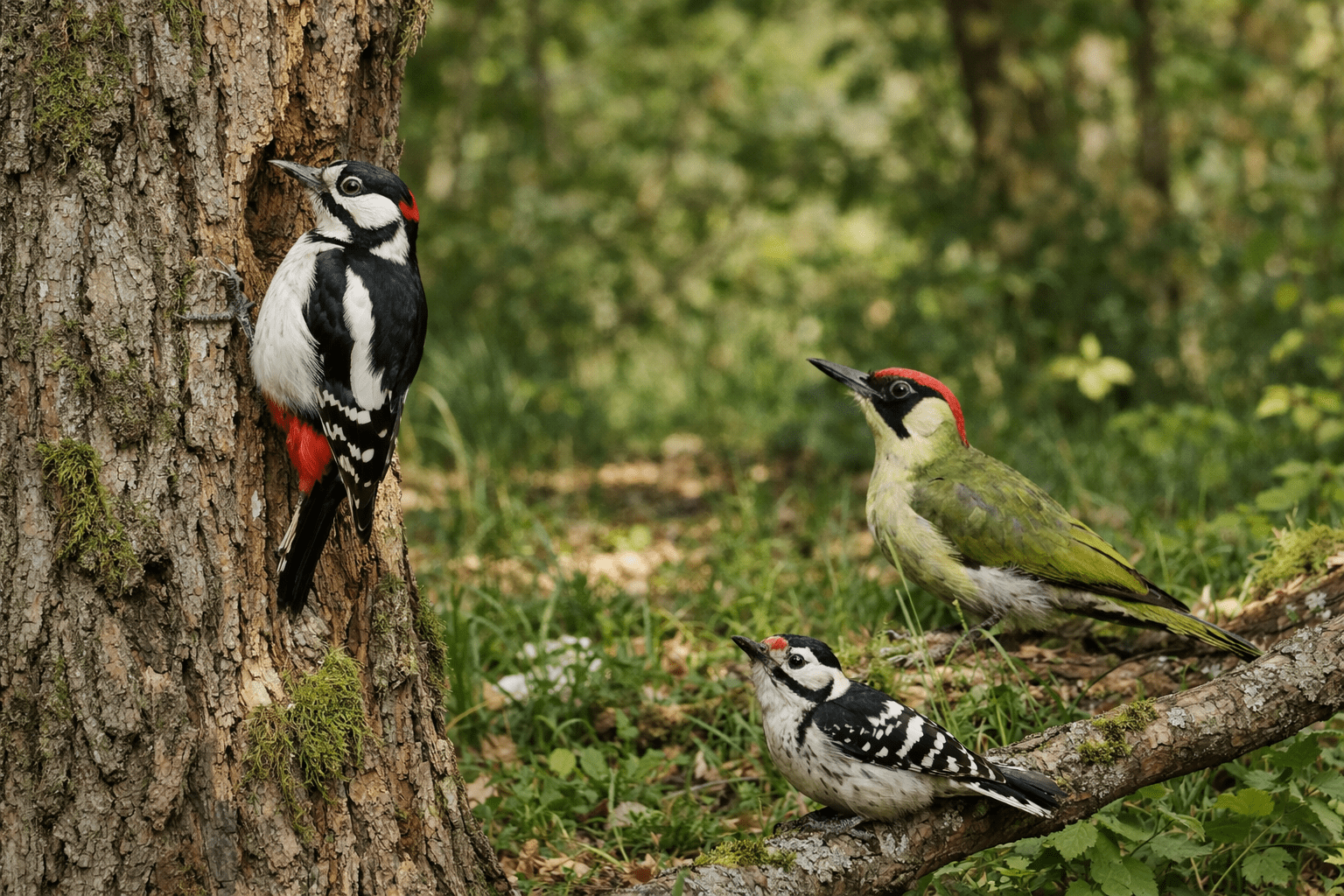

| Drummers of the Woodland Few birds are as instantly recognisable as woodpeckers. Whether it’s the sudden burst of rapid drumming echoing through trees or a flash of green lifting from a lawn, woodpeckers bring sound, movement, and character to Britain’s landscapes. They are birds shaped by trees, dependent on woodlands yet surprisingly adaptable, and deeply woven into the health of our ecosystems. Britain is home to three native woodpecker species: the Great Spotted Woodpecker, the Green Woodpecker, and the much rarer Lesser Spotted Woodpecker. Each has its own habits, personality, and place in the countryside, from dense woodland to suburban gardens and parkland. Why Woodpeckers Peck Woodpeckers peck for three main reasons: to find food, create nest holes, and communicate. Contrary to popular belief, most drumming isn’t about feeding at all. It’s a form of messaging — a way of announcing territory and attracting a mate. Each species has a distinct rhythm and tempo, turning dead branches and resonant trunks into natural instruments. Their skulls are specially adapted to absorb impact, and their strong neck muscles allow repeated strikes without injury. Long, barbed tongues help them extract insects hidden deep inside wood, making them highly effective natural pest controllers. The Great Spotted Woodpecker The most familiar and widespread of Britain’s woodpeckers, the Great Spotted Woodpecker is a confident, adaptable bird found in woodland, parks, orchards, and gardens. Its bold black-and-white plumage, red under-tail, and distinctive bounding flight make it relatively easy to identify. Great Spotted Woodpeckers feed mainly on insects and larvae found beneath bark, but they are opportunistic and will also eat seeds, nuts, and even bird feeders in winter. Their sharp “kick” call and rapid drumming are common sounds throughout much of the year. They excavate nest holes in dead or decaying trees, often choosing softer wood. These holes are rarely reused by the woodpeckers themselves, but once abandoned they become vital nesting sites for other birds such as tits, nuthatches, and even some small mammals. In this way, Great Spotted Woodpeckers act as quiet architects of woodland biodiversity. The Green Woodpecker Larger and more secretive, the Green Woodpecker is often heard long before it is seen. Its unmistakable laughing call — sometimes described as a loud “yaffle” — carries across open countryside, lawns, and woodland edges. Unlike other woodpeckers, the Green Woodpecker spends much of its time on the ground. Ants make up a huge part of its diet, and it uses its long, sticky tongue to probe anthills and soil. This feeding style explains why Green Woodpeckers are frequently spotted on short grass rather than clinging to tree trunks. Their green plumage blends remarkably well into leafy surroundings, offering camouflage despite their size. They nest in trees, usually choosing older trunks with softer wood, and prefer quieter areas with a mix of woodland and open feeding ground. Green Woodpeckers are an excellent indicator of healthy grassland ecosystems, where ants are plentiful and soil remains undisturbed. The Lesser Spotted Woodpecker The Lesser Spotted Woodpecker is Britain’s smallest and most elusive woodpecker — and sadly its numbers have declined significantly. Many people may never see one, even if they live near suitable habitat. About the size of a sparrow, this delicate bird favours mature woodland, old orchards, and areas with plenty of dead branches high in the canopy. Unlike its larger cousin, it avoids feeders and is rarely seen at ground level. Its drumming is softer and faster than that of the Great Spotted Woodpecker, often mistaken for insects or distant tapping. Males have a small red crown, while females lack red entirely. The decline of the Lesser Spotted Woodpecker is thought to be linked to the loss of old trees, tidier woodland management, and reduced insect populations — a reminder of how important natural decay and habitat variety truly are. Woodpeckers and the Health of Woodlands Woodpeckers are often described as keystone species because their actions benefit many others. By creating nest cavities, controlling insect populations, and relying on deadwood, they encourage a more natural, balanced environment. A woodland without dead trees may look neat, but it is often quieter, poorer in wildlife, and less resilient. Woodpeckers thrive where fallen branches, rotting trunks, and mature trees are allowed to remain. Even in gardens, leaving an old tree stump, allowing ivy to grow, or planting native trees can create future habitat. Woodpeckers reward patience and a slightly wilder approach to land management. Woodpeckers in Gardens and Towns While woodpeckers are woodland birds at heart, some have adapted well to human spaces. Great Spotted Woodpeckers are increasingly common visitors to gardens, especially during colder months. Their presence often surprises people, bringing a sense of wildness right to the back fence. Occasionally, drumming on sheds, fence posts, or guttering can cause concern, but this behaviour is usually seasonal and short-lived. Providing alternative feeding areas and avoiding disturbance during spring nesting can help minimise conflict. Living Alongside the Drummers Woodpeckers remind us that sound is part of nature’s language. Their drumming marks the seasons, their calls echo territorial boundaries, and their presence signals healthy trees and thriving insect life. By valuing old trees, resisting over-tidiness, and allowing nature a little space to age naturally, we make room not just for woodpeckers, but for the countless species that depend on them. In a world that often moves too fast, the steady rhythm of a woodpecker at work is a reminder that nature builds its homes one careful tap at a time. |

People around here seem to get very excited about woodpeckers – especially red-headed ones – I just looked up rare woodpeckers and I must admit they are quite beautiful.

LikeLiked by 1 person

They truly are lovely Grace, l too get excited when l see them, as they are oft shy and don’t like being seen.

LikeLiked by 1 person