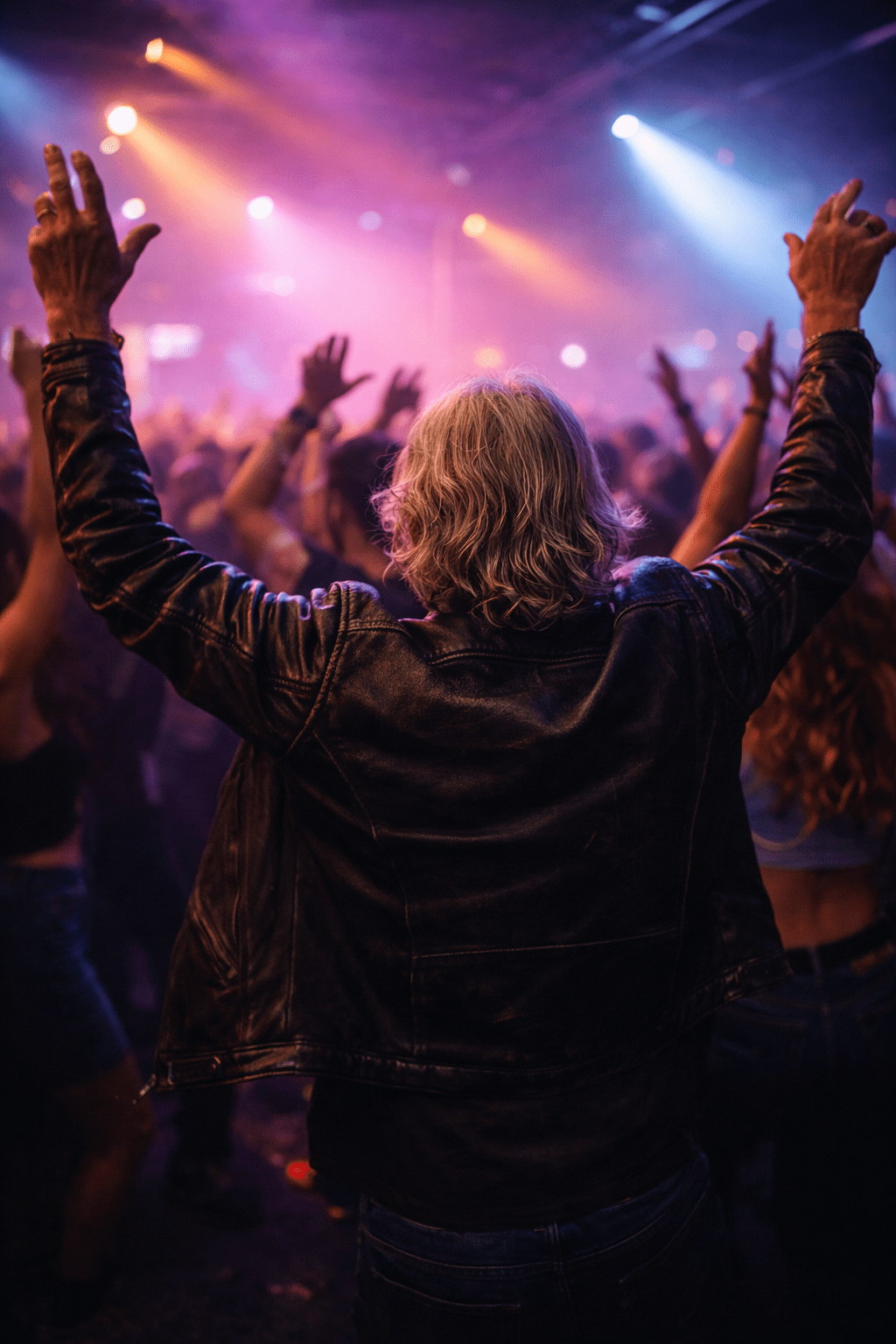

| Why Electronic Music Still Moves Me There comes a point in life where people start to expect you to quieten down. Not necessarily because you want to, but because you’ve reached an age where enthusiasm, physical expression, and intensity are supposed to soften into something more restrained. I’ve never found that expectation convincing. Especially when it comes to music. Electronic music has stayed with me not as a phase, not as nostalgia, and certainly not as something I’m “holding onto.” It has remained because it still works—on the body, on the mind, on the internal rhythm that doesn’t disappear just because the calendar keeps turning. I’ve been asked why, in my sixties, I’m still listening to music with heavy beats, long builds, dark edges, and hypnotic repetition. Why do I still move the way I do when it comes on? The simple answer is that the music never stopped speaking to me. The longer answer is that it never belonged to youth in the first place. When electronic music first cut through the noise of guitars and traditional song structures, it felt like a shift rather than a rebellion. It wasn’t about image, fashion, or frontmen. It was about sound as texture, rhythm as architecture, repetition as meaning. You didn’t have to be told how to feel. You were invited to feel it directly, physically, without translation. That directness matters. It always has. Electronic music bypasses explanation. It doesn’t rely on storytelling or lyrical persuasion. It doesn’t insist you identify with a persona or adopt a mood. Instead, it creates a space—sometimes vast, sometimes claustrophobic—where the listener fully immerses themselves in the experience. That relationship doesn’t weaken with age. If anything, it deepens. The body understands rhythm long before the intellect starts to interfere. Repetitive beats regulate breathing, movement, and focus. They give the nervous system something steady to lean into. Over time, most people are trained to ignore that instinct. Stillness becomes a virtue. Containment becomes maturity. Expression is tolerated only if it’s controlled, tasteful, and brief. Electronic music refuses that bargain. It repeats because repetition works. It builds slowly because anticipation is part of the pleasure. It doesn’t rush resolution because tension is not a problem to be fixed—it’s something to inhabit. That approach mirrors real life far more honestly than the neat arcs we’re usually offered. Moving to this kind of music isn’t a performance. It’s not about dancing well or being seen. It’s about letting the body do what it already knows how to do when it’s given the right stimulus. Head movement, arm swings, grounding through the feet—these are not signs of regression. They’re signs of a system discharging energy rather than storing it. Ageing doesn’t remove the need for that. It increases it. What tends to change is permission. People become self-conscious about movement. They worry about how it looks, what it implies, and whether it’s appropriate. Music becomes something to consume politely rather than inhabit fully. When someone doesn’t follow that script—when they still move freely later in life—it can make others uncomfortable. That discomfort says more about what they’ve suppressed than what I’m doing. Electronic music has always been oddly democratic. In dark rooms and warehouse spaces, labels dissolve. Age, background, status—none of it matters once the beat takes over. There’s no spotlight. No hierarchy. Just a shared physical response to sound. That environment doesn’t age out. If anything, it becomes more precious as life fills up with roles and responsibilities. I’m not chasing youth. I’m maintaining continuity. There’s a difference between clinging and continuing. Clinging is fear-based. It’s about denial and refusal to accept change. Continuing is about recognising what still works and refusing to discard it simply because it doesn’t fit someone else’s idea of how ageing should look. This music still centres me. It still clears mental clutter. It still pulls me into the present moment faster than almost anything else. That’s not nostalgia. That’s a function. The darker edges of electronic music—the minor keys, the tension, the stripped-back intensity—often get misunderstood as aggressive or bleak. I’ve always found the opposite. They’re honest. They don’t force optimism. They allow complexity without commentary. There’s room for weight, for ambiguity, for unresolved feeling. That emotional openness is rare, and it’s something many people lose access to as they get older, not because it’s gone, but because they’re discouraged from engaging with it. I never saw a reason to step away from that. There’s also something quietly defiant about refusing to shrink. Staying physically expressive, emotionally responsive, and sensorially alive in later life is a form of resistance—gentle, personal, and non-performative. It doesn’t ask for approval. It doesn’t need justification. It simply continues. When I listen to electronic music now, I hear more than I did when I was younger. I notice subtleties. I appreciate patience. I understand restraint. Long tracks make more sense, not less. The absence of lyrics feels like space rather than emptiness. Experience hasn’t dulled the impact. It’s refined it. If anything, this music has aged better than most cultural expectations around it. So when people ask why I still listen, still move, still respond, I don’t feel the need to defend it. I’m not making a statement. I’m responding to something that still works, still resonates, still does exactly what it always did. The beat never aged. Maybe that’s because it was never meant to. |

Unless stated, featured images are my own work, created independently or with the assistance of AI.

If it pleases you than why not listen to it. ♥️

LikeLiked by 1 person

Precisely 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

My philosophy is that when we cross 40-50, we should not be influenced by what others think of our choices.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very true, very Bridget Jones Sadje 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lol 😂

LikeLiked by 1 person