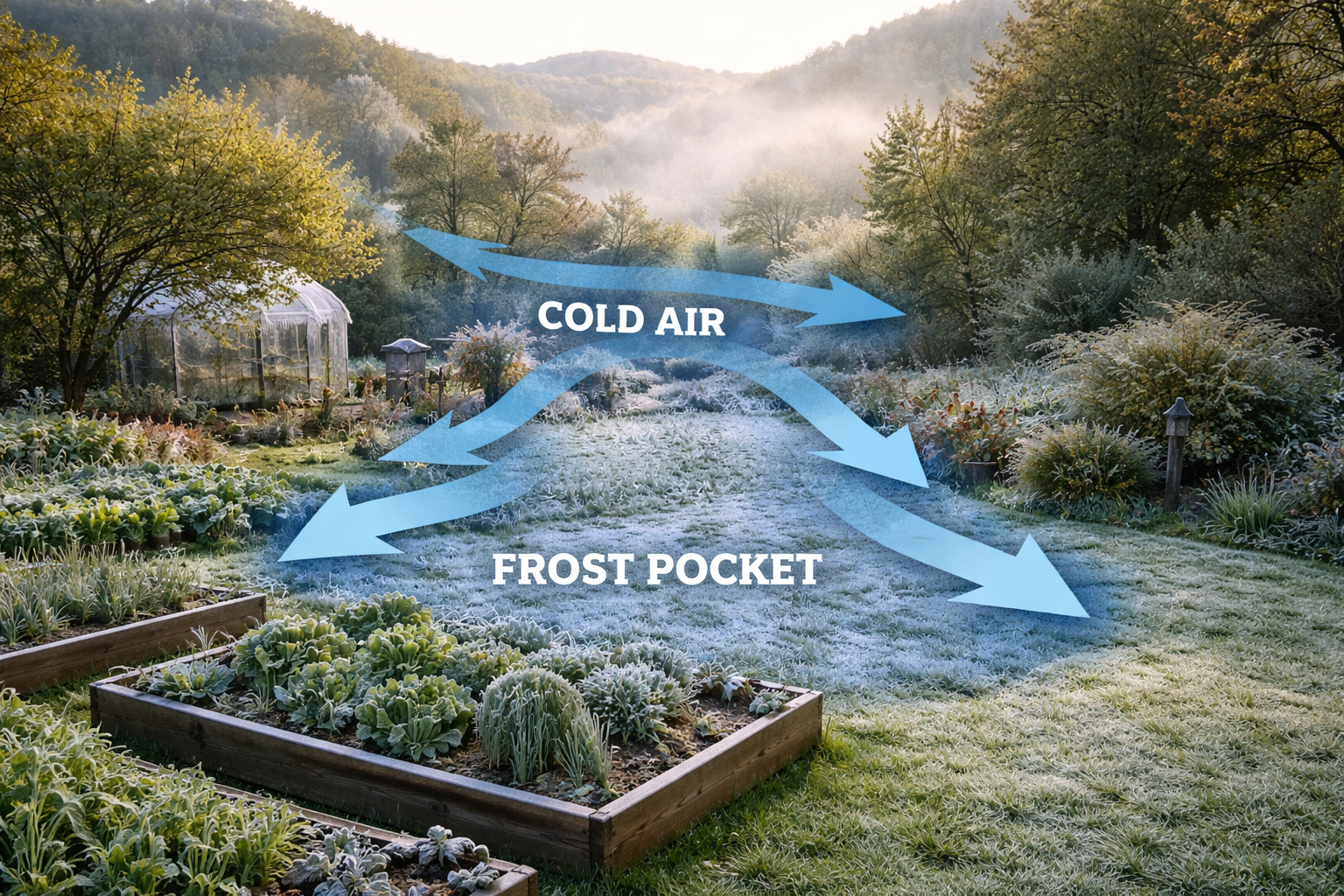

| How They Shape Your Garden Frost damage is one of the most misunderstood challenges in gardening. Many gardeners assume frost risk is determined purely by regional climate or overnight temperatures, but in reality, what happens within the boundaries of your own garden can matter just as much. Frost pockets and cold air movement play a decisive role in where plants struggle, survive, or thrive, often explaining why one bed fails repeatedly while another just metres away performs well year after year. Understanding how cold air behaves is not just theoretical knowledge. It is a practical skill that allows gardeners to work with their site rather than constantly fighting it. Once you learn to read frost patterns, plant losses decrease, winter resilience improves, and garden planning becomes far more strategic. What Is a Frost Pocket? A frost pocket is a low-lying area where cold air naturally collects, creating colder conditions than those in the surrounding area. Cold air is heavier than warm air, so as temperatures drop in the evening, it flows downhill and settles in dips, hollows, and enclosed spaces. These areas can be several degrees colder than higher ground nearby, even within the same garden. Frost pockets are not always obvious during the day. A garden may look flat or gently sloped, yet still contain subtle depressions where cold air gathers. Lawns at the bottom of a slope, beds beside solid fences, enclosed courtyards, and the base of retaining walls are all common frost-collecting zones. Importantly, frost pockets can experience frost even when the general forecast predicts none. This is why gardeners often feel caught out by unexpected damage to tender plants while neighbours remain unaffected. How Cold Air Moves Through a Garden Cold air behaves much like water. It flows downhill, follows the path of least resistance, and pools where it cannot escape. On calm, clear nights, this movement becomes more pronounced because there is no wind to mix warmer air back into low-lying areas. Slopes encourage cold air drainage, which is why gentle hillsides often avoid severe frost despite being more exposed. Flat gardens, on the other hand, can trap cold air if surrounded by hedges, fences, walls, or buildings that block its escape route. Hard surfaces such as paving and walls absorb heat during the day and release it slowly overnight, which can help reduce frost nearby. Conversely, open soil, lawns, and shaded ground cool quickly, encouraging frost formation. Understanding this flow allows gardeners to identify danger zones and safer microclimates within the same plot. Recognising Frost Patterns in Your Garden The clearest indicator of a frost pocket is repeated damage in the same location. If certain plants fail every winter despite being considered hardy, or if frost lingers longer on one area of lawn in the morning, cold air pooling is likely the cause. Early morning observation is one of the most valuable tools available to gardeners. Watching where frost forms first, where it melts last, and how it behaves across different areas reveals more than any textbook explanation. Signs to look for include darker, water-soaked foliage after frost, uneven lawn recovery in spring, and delayed growth in certain beds compared to others. These clues build a frost map unique to your garden. Why Frost Pockets Matter More Than Air Temperature Frost damage occurs at the plant level, not at weather-station height. Official temperature readings are taken well above ground, whereas plants experience temperatures closer to the soil surface, where cold air tends to concentrate. This means a forecast of 2°C can still result in ground-level frost in a pocket, while an exposed slope may remain frost-free. Tender growth, blossom, and young shoots are especially vulnerable because they sit directly in the coldest air layer. For gardeners growing fruit, vegetables, or ornamental plants with early growth cycles, frost pockets can significantly affect yields, flowering, and long-term plant health. Designing and Planting With Cold Air in Mind Once frost pockets are identified, they can be managed rather than feared. The most effective strategy is plant placement. Hardy, frost-tolerant plants should be planted in low areas, while tender or early-flowering species are best positioned on slightly raised ground or near heat-retaining structures. Raised beds are particularly useful in frost-prone gardens. Even a small lift above ground level can place plants out of the coldest air layer. Similarly, planting on the upper side of a gentle slope can make a noticeable difference to winter survival. Avoid placing dense barriers directly across slopes, as these can trap cold air upslope and worsen frost damage. Where boundaries are necessary, allowing small gaps at ground level can help cold air drain away naturally. Using Structures and Materials to Reduce Frost Risk Walls, fences, and buildings can be both a problem and a solution. Solid structures block cold air movement but also store heat, creating warmer microclimates on their sun-facing sides. South- and west-facing walls are particularly valuable for protecting tender plants. Mulching soil helps stabilise ground temperatures and reduces rapid overnight heat loss. Organic mulches also improve soil structure, allowing better drainage and further reducing frost severity. Temporary protection, such as fleece or cloches, is most effective when used selectively in known frost pockets rather than applied indiscriminately across the whole garden. Long-Term Benefits of Understanding Frost Movement Gardens designed with cold air movement in mind are more resilient, require less intervention, and experience fewer seasonal losses. Instead of reacting to frost damage each year, gardeners can make informed decisions that align with the natural behaviour of their site. This approach also encourages a deeper connection with the garden. Observing frost patterns sharpens awareness of microclimates, seasonal rhythms, and subtle landscape changes that often go unnoticed. Ultimately, frost pockets are not flaws in a garden but features to be understood. When respected and planned for, they become part of a balanced, responsive garden system rather than an ongoing source of frustration. |

Frost Pockets & Cold Air Movement