| Living with Old Man’s Beard on a Wall Some plants ask politely to be included in a garden, while others arrive. They turn up unannounced, settle themselves into corners you didn’t offer, and then act mildly offended when you question their presence. Clematis vitalba — Old Man’s Beard, Traveller’s Joy, goat’s beard, if you grew up hearing it called that — belongs firmly in the second group. It is a plant that does not really understand the difference between wild and garden. Or rather, it understands it perfectly well and ignores it. Put it next to a wall, and it will treat the wall as a hedgerow. Give it time, and it will treat the hedge as a woodland edge. Leave it longer still, and it begins to behave like a small ecosystem in its own right: shade-maker, moisture-trapper, ladder, curtain, nest site, and eventually burden. I have met it in many forms and draped elegantly over a sun-warmed chalk bank and tangled in roadside scrub where no one has intervened in decades. And, increasingly, clamped onto old garden walls, where its strength and persistence feel both impressive and faintly threatening. It is often admired right up until the moment it becomes unmanageable. Which is usually the moment someone realises that admiration alone does not constitute stewardship. A wall is not a tree. One of the quiet misunderstandings that leads to trouble with Clematis vitalba is the assumption that a wall is simply a vertical field. If a plant is happy scrambling over hedges and trees in the wild, it will behave similarly when given stone instead of bark. It won’t. Trees bend. Walls do not. Trees shed moisture. Walls hold it. Trees grow away from their climbers, thickening and strengthening in response. Walls stay exactly as they are, slowly eroding where water and plant matter linger too long. Old Man’s Beard evolved to scramble, not to cling delicately. It doesn’t tiptoe. It loops, hooks, and leverages. On a hedge, this is mostly harmless. On a mature tree, it becomes a negotiation. On a wall — particularly an old, soft-mortared one — it is a structural conversation the wall cannot answer. The plant in its mature state is not light. Those rope-thick stems that look picturesque when stripped of leaves in winter carry real weight. Add a season’s worth of foliage, rain, and wind, and the load multiplies quietly, year after year. By the time someone notices, it is usually not because the plant looks too vigorous. It’s because the wall beneath it has begun to complain. Winter honesty Winter is when Clematis vitalba tells the truth. Without leaves, without flowers, without the softening effect of green abundance, what remains is structure. And structure is where decisions must be made. In winter, you see just how much of the plant is no longer doing anything useful. You see the deadwood. The self-strangling loops. The growth that once flowered but now exists only because no one has intervened. You also see, often quite starkly, how little of the plant is actually anchored at the base compared to how much of it has wandered elsewhere. This is where a common hesitation creeps in. The idea that cutting hard is an act of violence. That severe pruning is somehow a betrayal of the plant’s natural inclination. That leaving it alone is kinder. In practice, leaving Clematis vitalba alone is not kindness. It is abdication. The difference between wildness and neglect One of the lazier gardening myths is that wild plants prefer neglect. What they actually prefer is clarity. In the wild, clarity is enforced by competition, grazing, windfall, and collapse. In gardens, clarity has to be imposed deliberately. Old Man’s Beard is often described as “vigorous” or “free-spirited”, which are words we reach for when we don’t want to say “indiscriminate”. It does not choose carefully where it grows. It chooses where it can. If nothing stops it, it will take everything it is offered and then look for more. Hard pruning, when done thoughtfully, is not an attempt to civilise the plant. It is an attempt to reset the relationship. To return the plant to a scale where its strengths can be appreciated without allowing its weaknesses to cause damage. Cutting back as an act of listening A hard cut on Clematis vitalba is often framed as a technical decision: how low, how much, how often. In reality, it is an observational one. You cut hard because the plant is telling you it needs space to restart. You cut because the growth has outrun its usefulness. You cut because the wall beneath it needs light and air again. You cut because you want to see what the plant actually does when given a clear beginning rather than an inherited mess. This clematis flowers on new growth. That fact is well known, but it is often treated as permission rather than an invitation. The invitation is this: start again and see what happens. When cut back to a foot or two above ground, the plant responds with an almost startling honesty. New shoots are purposeful. Growth is directed. The mass of confused old wood is gone, and what replaces it feels intentional rather than accidental. There is a confidence to a plant that has been properly reset. It no longer needs to prop itself up on decades of dead ambition. The wall breathes again. One of the most immediate effects of a hard cut has nothing to do with the plant at all. It is the wall. Light reaches the stone that has not seen it in years. Air moves through joints that have been damp and shaded. Moss retreats from places where it had begun to feel permanent. The wall does not look newly exposed so much as relieved. This is particularly important with older walls, where lime mortar relies on breathability. Plants that mat tightly against stone disrupt that process. They create microclimates that favour decay. Cutting back is not aesthetic interference; it is maintenance. It is also revealing. Walls often tell their own stories once uncovered — repairs, scars, stone changes. A plant that permanently obscures this prevents the garden from acknowledging its own history. A plant that rewards restraint, not indulgence There is a temptation, after a hard cut, to let the plant run unchecked again out of guilt or optimism. This is where people fall into a cycle: severe cut, explosive growth, years of avoidance, another severe cut. Cle? Matis Vitalba does best when given boundaries early. Not rigid ones, but clear ones. A few strong framework stems are trained deliberately. Excess is removed before it becomes embedded. Growth is redirected rather than tolerated. This is less dramatic than letting it riot and then intervening heroically, but it produces a better relationship. The plant remains expressive without becoming oppressive. Rethinking “natural” climbers There is a broader assumption at play here, one worth gently challenging: that native or wild climbers are inherently better suited to informal gardens and therefore require less management. Suitability is not about origin. It is about behaviour in context. A plant that evolved to move freely across hedgerows may be a poor fit for a confined garden wall unless actively managed. Conversely, some cultivated climbers are far more restrained and predictable. Choosing Clematis vitalba — or inheriting it — is not wrong. Expecting it to behave without guidance is. Knowing when to let go There is also an unspoken question that arises after any hard cut: should this plant stay at all? Sometimes the answer is yes. Sometimes, after resetting, the plant earns its place. It flowers well. It softens the wall without burdening it. It becomes part of the garden rather than its dominant feature. Sometimes the answer is no. The plant resents restraint. The wall continues to suffer. The gardener continues to negotiate rather than enjoy. Removing Clematis vitalba entirely is not a failure. It is a recognition that not every plant suits every place indefinitely. Gardens are allowed to change their minds. The quiet authority of experience There is a difference between advice given theoretically and decisions made after years of cutting tangled wood out of awkward corners. Experience teaches you that plants are remarkably forgiving, and that gardeners often underestimate both their resilience and their need for intervention. Hard pruning feels dramatic only until you have done it a few times and watched what follows. Regrowth does not come with resentment. It comes with clarity. The plant does not remember how large it once was. It only responds to where it is now. What remains after the cut Once the debris is cleared and the structure revealed, what remains is not emptiness. It is potential. Space for air. Space for light. Space for a relationship that is not based on avoidance. Old Man’s Beard, when handled with confidence rather than fear, can be a generous plant. It flowers freely. It moves beautifully in the wind. It belongs to the landscape rather than sitting atop it. But it does not want to be left alone. It wants to be understood. |

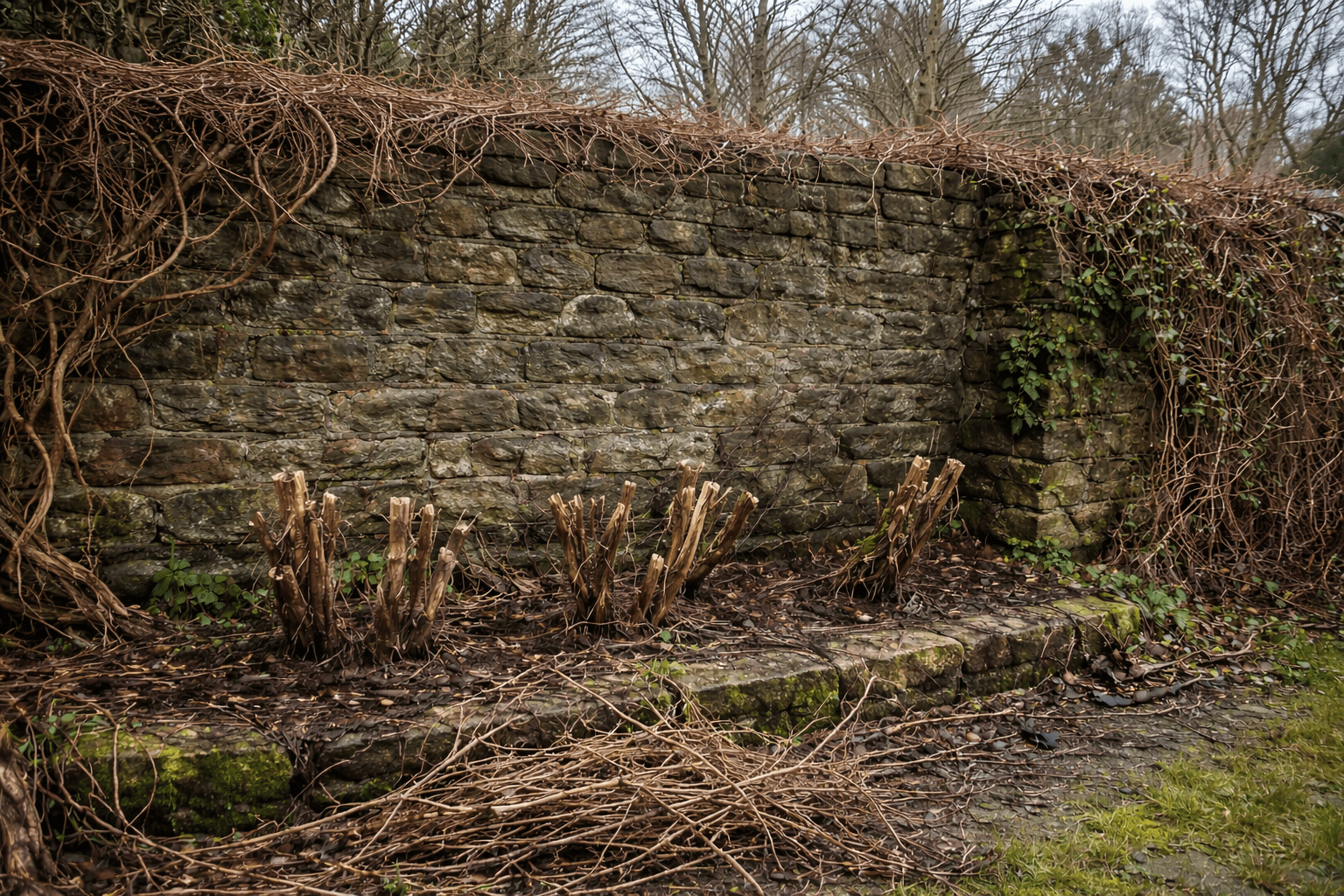

| Client’s Old Man’s Beard Clematis that requires cutting back, however they wish for a lot of the ornamental root to be kept in situ. |

| Companion note: when the roots are part of the picture Not everyone cuts Old Man’s Beard down to disappear. And not everyone should. One of the quieter reasons some gardeners hesitate before a complete reset is the plant’s woody framework itself. Given time, Clematis vitalba develops twisted, rope-like stems that can read less as growth and more as structure — almost sculptural in winter. On old walls especially, these contorted uprights can feel closer to driftwood or old vine than to something merely overgrown. There are gardens where this matters. Where the wall is already expressive, and the plant’s exposed framework adds to that sense of age rather than detracting from it. In those settings, keeping a small number of established, characterful stems can be a deliberate choice rather than a compromise. The plant is still cut hard elsewhere, but its most interesting wood is left visible, treated almost as a permanent feature. This approach asks more of the gardener, not less. Retained stems need regular watching. New growth must be directed early. The line between character and congestion is thin, and once crossed, it is hard to reverse without losing the very thing you meant to preserve. But when it works, it produces something rare: a climber whose roots and framework are ornamental in their own right, even out of leaf. The wall carries a sense of continuity through winter, and the plant feels integrated rather than seasonal. It is not the right decision everywhere. It depends on scale, wall condition, and the patience of the person who will be managing it next year — and the year after that. But it is worth acknowledging that restraint can take more than one form, and that sometimes the most honest cut is not the lowest possible one, but the one that leaves behind what genuinely deserves to stay. |

| About our writing & imagery Most articles reflect our real gardening experience and reflection. Some use AI in drafting or research, but never for voice or authority. Featured images may show our photos, original AI-generated visuals, or, where stated, credited images shared by others. All content is shaped and edited by Earthly Comforts, expressing our own views. |