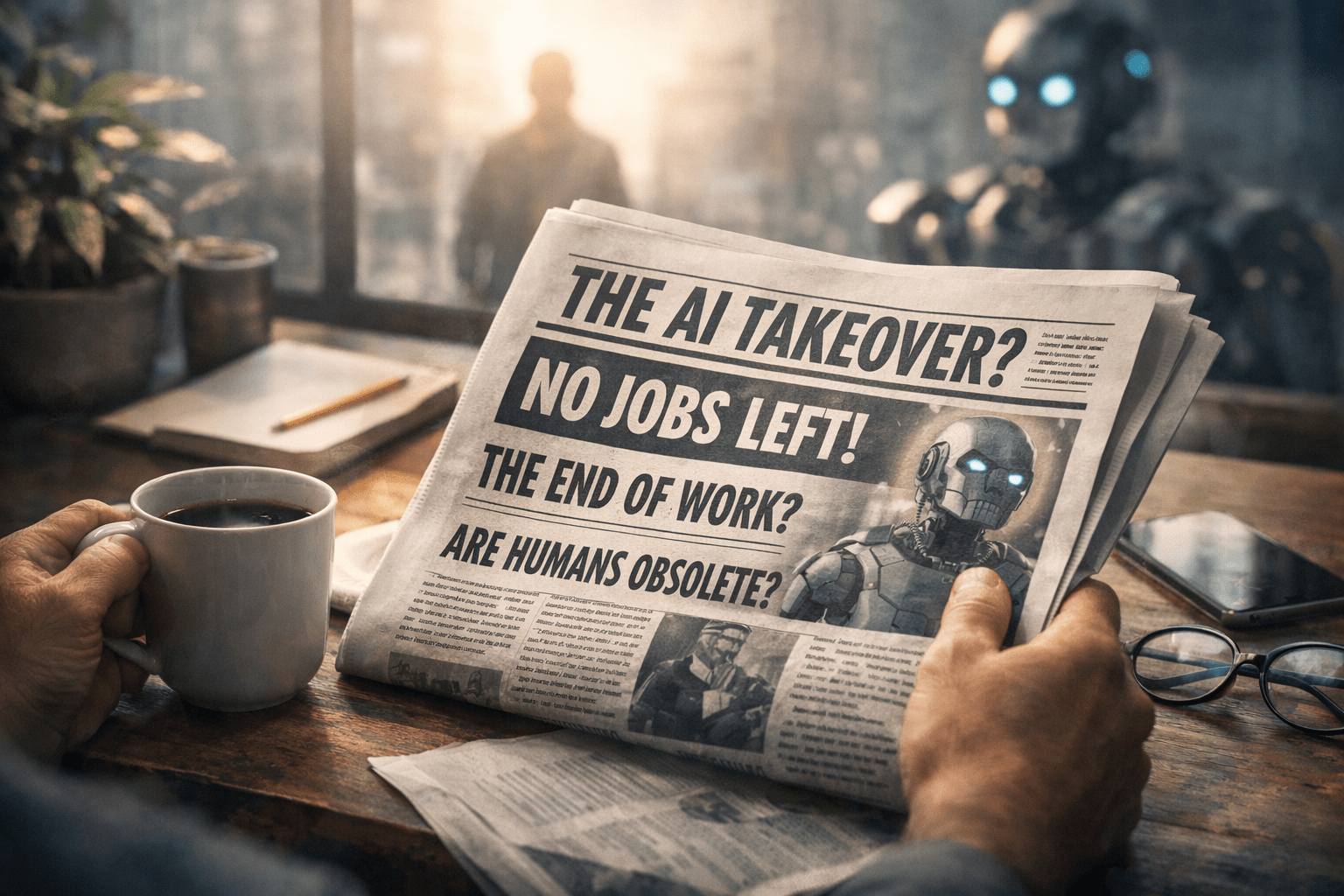

| How Social Newspapers Are Framing AI Every so often, a headline appears that gives you pause, not because it feels particularly insightful, but because it feels carefully weighted. Recently, The Independent ran a piece suggesting a future in which people are paid to do “nothing” because AI has rendered work obsolete. It’s the kind of framing that invites an immediate reaction — curiosity, unease, even a flicker of relief — and that reaction seems to be doing more of the work than the idea itself. It’s difficult not to notice how often AI is now presented through the lens of loss. Loss of jobs, loss of purpose, loss of necessity. The language tends toward absolutes: nobody works, nothing to do, the end of contribution as we know it. These are powerful words, but they are also flattening ones. They remove context, nuance, and most importantly, agency. They imply inevitability, as though the future simply happens to us rather than being shaped by millions of small human decisions. Social newspapers exist in a very different ecosystem than they once did. Attention has become the primary currency, and fear remains one of the fastest ways to secure it. AI, complex and poorly understood by most, makes an ideal vehicle for that fear. It touches money, identity, usefulness, and worth — all the quiet questions people already carry. In that environment, balanced exploration struggles to compete with dramatic certainty, even when that certainty is largely imagined. What often goes unsaid in these stories is that technological change has never erased work itself. It has always shifted where value sits. The plough, electricity, mechanisation, and the internet — each altered the shape of labour without extinguishing the human need to contribute. Yet current narratives around AI frequently skip that historical rhythm and jump straight to a vision of redundancy, as if the act of being useful were a technical problem waiting to be solved. There is also a quiet irony in how this fear is distributed. Much of the anxiety appears concentrated in abstract, screen-based worlds, where tasks are already detached from place and outcome. Meanwhile, work rooted in physical presence, care, stewardship, and continuity rarely features in these conversations. Not because it is unimportant, but because it does not translate easily into sensational language. A machine can generate, analyse, and predict, but it cannot take responsibility for living systems, show up consistently in the real world, or build trust over time. Those forms of work continue quietly, largely unnoticed by the headlines. When newspapers repeatedly suggest that people will no longer be needed, something subtle begins to shift. Work stops being framed as a contribution or service and starts being framed as an inconvenience, a relic, something we are meant to escape. That narrative has consequences. Even before automation touches a job, it can erode the dignity of the job. AI itself is not the villain of this story. If anything, it acts as a mirror, reflecting which forms of work were already fragile and which were deeply anchored. It exposes systems that prioritise efficiency over resilience and abstraction over connection. At the same time, it quietly highlights the enduring value of work that is relational, place-based, and accountable. Perhaps the most revealing thing about these headlines is not what they say about the future, but what they reveal about the present. They speak to a media landscape that struggles to sit with uncertainty and prefers bold conclusions to honest questions. The future shaped by AI is unlikely to be one of universal idleness. It is far more likely to be uneven, human, adaptive, and shaped by those who keep turning up, take responsibility, and remain connected to the real world as the noise grows louder around them. That future may not generate many clicks, but it is far closer to reality than the idea of a world where nobody works. |

When Fear Gets the Click