| The Quiet Case Against Over-Mowing |

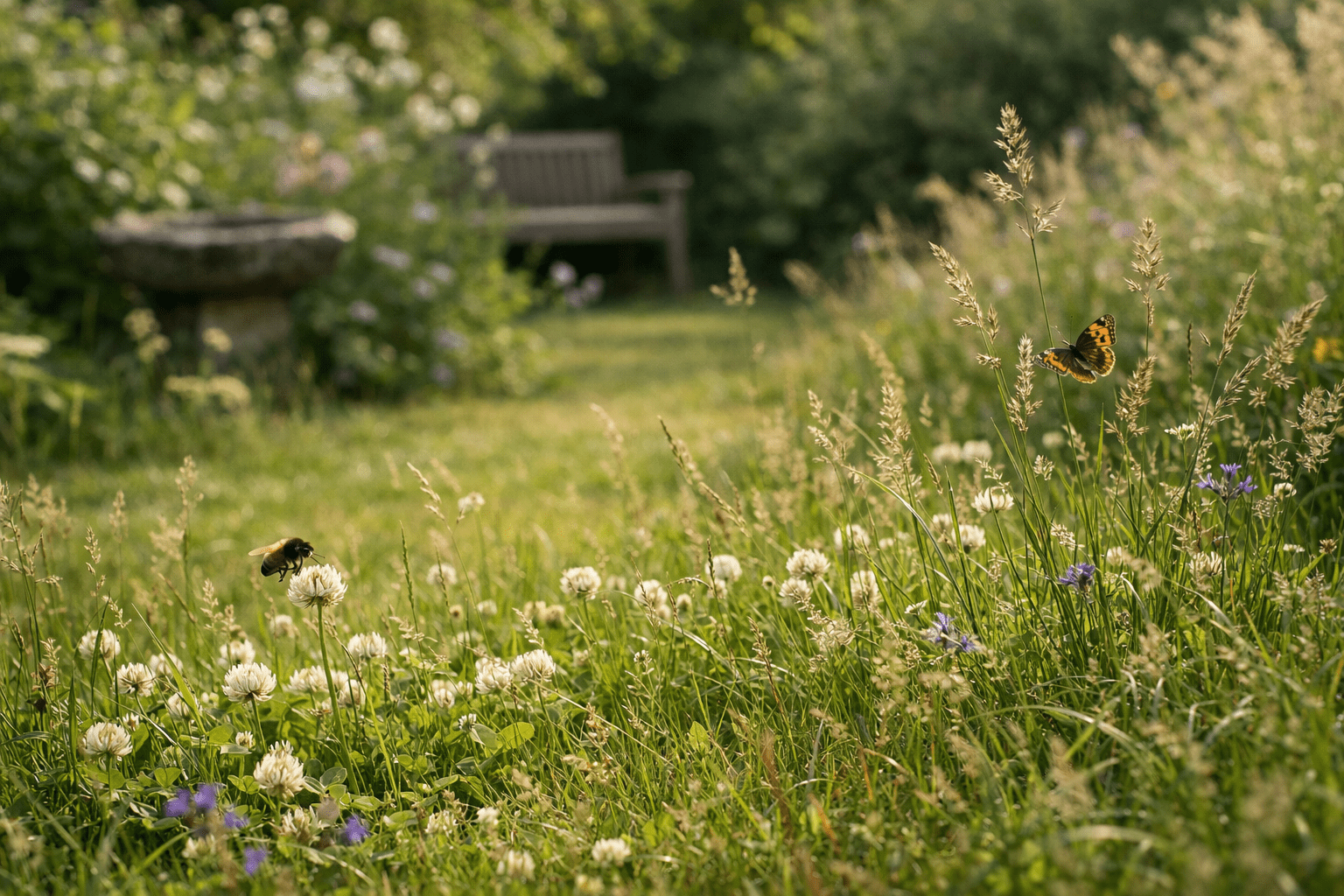

| There was a time when mowing felt like the centre of gardening. You cut, and you proved you cared. A neat lawn was the visible sign of effort, reliability, and order. It told neighbours you were keeping up. It told clients you were doing your job. But the longer I’ve worked with gardens—and the more the weather has shifted under our feet—the more that logic has started to feel thin. Not wrong, exactly. Just inherited. A habit passed down from a different climate, a different pace of life, and a different relationship with land. Over-mowing isn’t usually done with evil intent. It’s done because “that’s how lawns are kept”. Every fortnight, sometimes weekly. Rain or shine. Growth or no growth. The machine comes out, the grass is taken back, and the cycle repeats. What’s rarely asked is whether the lawn itself actually benefits from this rhythm—or whether we’re simply maintaining the appearance of care. When you slow down and pay attention, the lawn begins to answer that question for you. Growth is not a schedule. Grass does not grow according to a calendar. It responds to soil temperature, moisture, light levels, and recovery time. In early spring, it can surge almost overnight. In midsummer heat, it can stall completely. In shaded gardens, growth may be gentle all year. In exposed coastal plots, it might toughen and sit low, requiring infrequent cutting. Yet mowing schedules often ignore all of this. The mower turns up because it’s “time”, not because the grass has meaningfully changed. Over-mowing often begins here: cutting grass that hasn’t really grown, removing leaves that the plant was still using, and resetting the lawn back to recovery mode again and again. Grass that is constantly recovering never gets a chance to strengthen. Short grass, shallow roots One of the quiet truths of lawns is that what you see above ground mirrors what’s happening below. Frequent cutting encourages grass to invest in leaf replacement rather than root depth. Over time, this creates lawns that look tidy but behave poorly: quick to scorch, slow to recover, dependent on rain or intervention. Allow grass a little more height and time, and something shifts. Roots explore deeper layers of soil. Moisture lasts longer. The lawn becomes more resilient, not because it’s been fed or treated, but because it’s been allowed to behave like a plant rather than a surface. Over-mowing doesn’t just remove grass—it limits the lawn’s ability to look after itself. Soil doesn’t like being exposed. When grass is cut short, soil is left open to sun, wind, and heavy rain. In hot spells, this leads to rapid drying and cracking. In wet periods, bare patches compact and smear under foot traffic and machinery. Longer grass acts as a buffer. It shades the soil, slows evaporation, and softens the impact of rainfall. It creates a small but meaningful microclimate at ground level—cooler, more stable, and less hostile to life. Over time, lawns that are allowed to keep some cover tend to need less repair. The soil holds together better. Worms remain active closer to the surface. Structure improves quietly, without any dramatic intervention. Heat changes the rules. Hot summers have a way of exposing outdated habits. Cutting a lawn short in prolonged heat often looks fine for a few days, then fades, then browns, then struggles to recover. The damage isn’t always immediate, which makes the cause easy to miss. Grass under heat stress needs leaf area. It needs shade for its own crown. Removing that protection when temperatures are high is less maintenance than attrition. Over-mowing during heatwaves is one of the fastest ways to weaken a lawn for the rest of the season. Sometimes the most skilled decision is not to mow at all. Mixed lawns are not failed lawns. Many lawns now contain clover, daisies, self-heal, plantain, and other low-growing plants that previous generations would have tried to remove. These plants persist not because maintenance has slipped, but because they are well adapted to modern conditions. They fix nitrogen, tolerate compaction, flower in short gaps, and stay green in dry weather. Frequent mowing suppresses them just enough to prevent flowering without ever removing them. The result is a lawn that works harder and gives less back. Allowing a lawn to be mixed—and mowing less frequently—often results in better colour, better resilience, and a quieter kind of beauty. One that doesn’t shout, but holds. Wildlife lives in the margins Even small lawns play a role in local ecosystems. Insects use grass stems for shelter. Pollinators rely on fleeting flowers that appear between cuts. Birds forage where seed and movement exist. Over-mowing erases these opportunities before they properly begin. A lawn cut too often becomes ecologically blank—not because it’s hostile, but because it’s constantly reset. Leaving slightly longer intervals between cuts doesn’t turn a lawn into a meadow. It simply allows life to pass through. And in many gardens, that feels like enough. Recovery matters more than neatness. Lawns are walked on, sat on, and played on. Children run, pets circle, furniture shifts. Grass with more leaf area recovers faster from this use. Short, tightly cut grass has little capacity to bounce back. Over-mowing prioritises neatness over function. It assumes lawns exist primarily to be looked at, rather than used. In reality, most domestic lawns benefit from being a little forgiving, a little soft, a little robust. Functionally, longer grass wins. Thatch and compaction are often self-inflicted. Frequent mowing encourages shallow growth and fine clippings that sit at the surface. Over time, this contributes to thatch buildup and reduced air flow into the soil. Compaction follows, particularly where mowing equipment follows the same routes week after week. Ironically, the problems often blamed on “poor lawns” are created by trying too hard to perfect them. Less frequent mowing, combined with observation and occasional intervention, often produces better structure than constant cutting ever does. Noise, energy, and presence There is also the simple matter of impact. Mowing is noisy. It interrupts. It carries a physical and environmental cost, particularly when done out of habit rather than need. Gardens benefit from periods of stillness. So do the people living around them. Reducing mowing frequency doesn’t mean neglect—it means choosing presence over performance. Doing the work that matters, when it matters. The myth of the perfect lawn Perhaps the strongest reason to question over-mowing is the idea it’s built on: that a lawn must look a certain way to be healthy, cared for, or respectable. This idea has been remarkably durable, even as the climate, ecology, and pace of life have all changed. In practice, the healthiest lawns I see are rarely the ones cut most often. They are the ones that are observed, responded to, and occasionally left alone. Lawns that are treated as living systems rather than surfaces to be managed. Over-mowing promises control. What it often delivers is fragility. What experience teaches, slowly After enough seasons, patterns repeat themselves. Lawns cut less often hold colour longer. Lawns given recovery time cope better with extremes. Lawns allowed to be slightly imperfect tend to become more stable, not less. This isn’t an argument against mowing. It’s an argument against reflex. Against the idea that care must always look busy, or that restraint is neglect. Sometimes, the most professional choice a gardener can make is to leave the mower in the shed, watch the weather, and let the grass decide what it needs next. Not everything improves through repetition. Some things improve through attention. |

| About our writing & imagery Most articles reflect our real gardening experience and reflection. Some use AI in drafting or research, but never for voice or authority. Featured images may show our photos, original AI-generated visuals, or, where stated, credited images shared by others. All content is shaped and edited by Earthly Comforts, expressing our own views. |