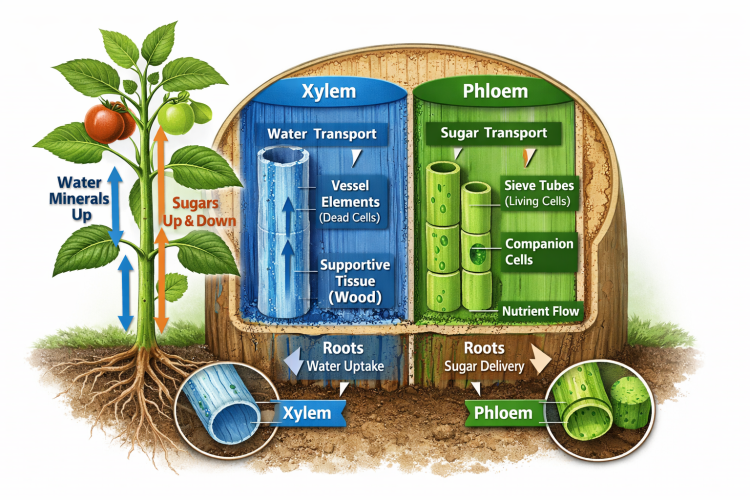

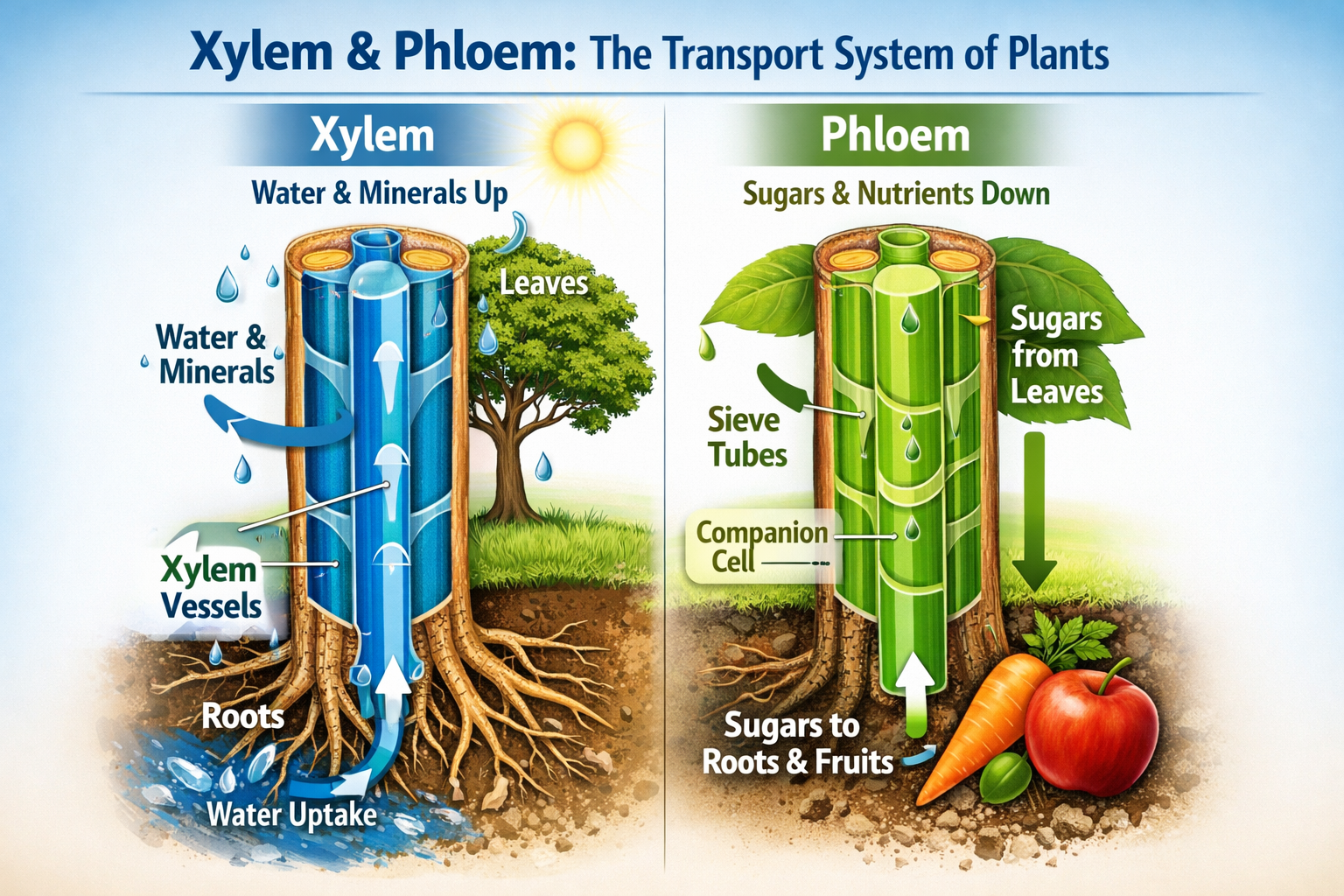

| The Hidden Transport System That Keeps Plants Alive Plants may appear still and simple on the surface, but inside them runs a highly organised transport network that rivals any engineered system. At the heart of this network are two specialised tissues: xylem and phloem. Together, they move water, minerals, sugars, and signals throughout the plant, enabling growth, repair, and survival. Understanding xylem and phloem helps explain how a tree lifts water metres into the air, how leaves feed roots, and why bark damage can slowly kill a plant. These tissues are not optional extras; they are essential infrastructure. What Are Vascular Tissues? Xylem and phloem are known as vascular tissues. “Vascular” simply means they are involved in transport. They form continuous pathways that run from roots to shoots to leaves, connecting every living part of the plant. Unlike animals, plants cannot move resources by pumping blood. Instead, they rely on physical forces, pressure differences, and the coordinated action of living cells. Xylem and phloem are structurally different, perform opposite directional roles, and rely on very different mechanisms. Xylem: The Water Highway Xylem is responsible for moving water and dissolved minerals from the roots upward through the plant. This upward-only movement is crucial, as water is needed in leaves for photosynthesis, cooling, and cell expansion. Most xylem cells are dead at maturity. This may sound counterintuitive, but it is key to their function. Hollow, reinforced cells form long, continuous tubes that allow water to move freely without resistance from cell contents. The thick walls are strengthened with lignin, making xylem rigid and supportive. Water movement in the xylem is mainly driven by transpiration. As water evaporates from leaf surfaces, it creates a pulling force that draws water upward from the roots. Cohesion between water molecules and adhesion to xylem walls keep the water column intact, even in tall trees. In addition to transport, xylem provides structural support. The same lignified tissue that carries water also helps plants stand upright. Wood is essentially secondary xylem, produced year after year as trees grow thicker. Phloem: The Nutrient Distribution Network Phloem carries sugars and other organic compounds produced during photosynthesis. Unlike xylem, phloem can transport materials both up and down the plant, depending on where resources are needed. Phloem tissue is living. Its main conducting cells, sieve tube elements, lack a nucleus but remain alive with the help of companion cells. These companion cells manage metabolism and actively control the loading and unloading of sugars. Substances that move through the phloem include sugars, amino acids, hormones, and signalling molecules. This makes phloem not just a food delivery system, but also a communication network that helps coordinate growth, flowering, and responses to stress. Movement in phloem relies on pressure flow. Sugars loaded into phloem at source tissues, such as leaves, draw in water by osmosis. This creates pressure that pushes sap toward sink tissues, such as roots, fruits, or growing shoots. Key Differences Between Xylem and Phloem Although xylem and phloem often sit side by side, their roles are very different. Xylem transports water and minerals upward only, while phloem distributes sugars in multiple directions. Xylem cells are dead and rigid; phloem cells are living and dynamic. Xylem movement is passive, driven by physical forces like evaporation and cohesion. Phloem movement requires energy, as sugars must be actively loaded and unloaded by living cells. Damage affects them differently. If xylem is disrupted, a plant struggles to supply water and quickly wilts. If phloem is damaged, starvation occurs more slowly as sugars fail to reach roots and growing tissues. How Xylem and Phloem Work Together Neither tissue works in isolation. Water delivered by xylem supports photosynthesis, which produces the sugars transported by phloem. Sugars are transported by the phloem from the root growth, which in turn improves water uptake in the xylem. This cooperation creates a continuous loop. When leaves produce more sugars, roots grow stronger. When roots absorb more water, leaves function better. The health of one system directly affects the other. Seasonal changes highlight this relationship. In spring, phloem transports stored sugars upward to fuel new growth before leaves are fully active. Later in the year, sugars flow downward to roots and storage tissues in preparation for winter. Why Girdling a Tree Is So Damaging Removing a ring of bark from a tree, known as girdling, demonstrates the importance of phloem. Bark contains phloem but not much xylem. When bark is removed, water can still move upward through xylem, so leaves may remain green for a time. However, sugars can no longer travel downward. Roots starve, die back, and eventually fail to supply water. The tree dies slowly, not from thirst, but from lack of energy. This delayed response often confuses people unfamiliar with plant transport systems. Xylem, Phloem, and Environmental Stress Environmental stress places heavy demands on both tissues. During drought, xylem water columns can break, forming air bubbles that block transport. Plants adapted to dry conditions often have narrower xylem vessels to reduce this risk. Phloem transport can be disrupted by cold, pests, or disease. Aphids, for example, feed directly on phloem sap, weakening plants by draining their energy supply. Some plant diseases spread through phloem, interfering with sugar movement and signalling. Understanding these vulnerabilities helps gardeners and growers diagnose problems more accurately and manage plants with greater care. Why This Matters for Gardeners and Growers A practical understanding of xylem and phloem improves pruning, watering, and overall plant care. Overwatering affects xylem function by reducing oxygen in the root zone. Poor leaf health limits phloem sugar production, weakening the entire plant. Healthy plants depend on balanced transport. Strong roots, active leaves, and intact stems all support the smooth flow of resources. When one part fails, the effects ripple through the entire system. The Quiet Engine of Plant Life Xylem and phloem operate silently and invisibly, yet every leaf, flower, and root depends on them. They allow plants to grow tall without pumps, to share resources across great internal distances, and to adapt to changing conditions. By understanding these tissues, we gain a deeper appreciation for how plants function as integrated, living systems. What appears simple on the outside is sustained by remarkable internal coordination, refined over millions of years of evolution. |