| Holding Rain Where It Falls |

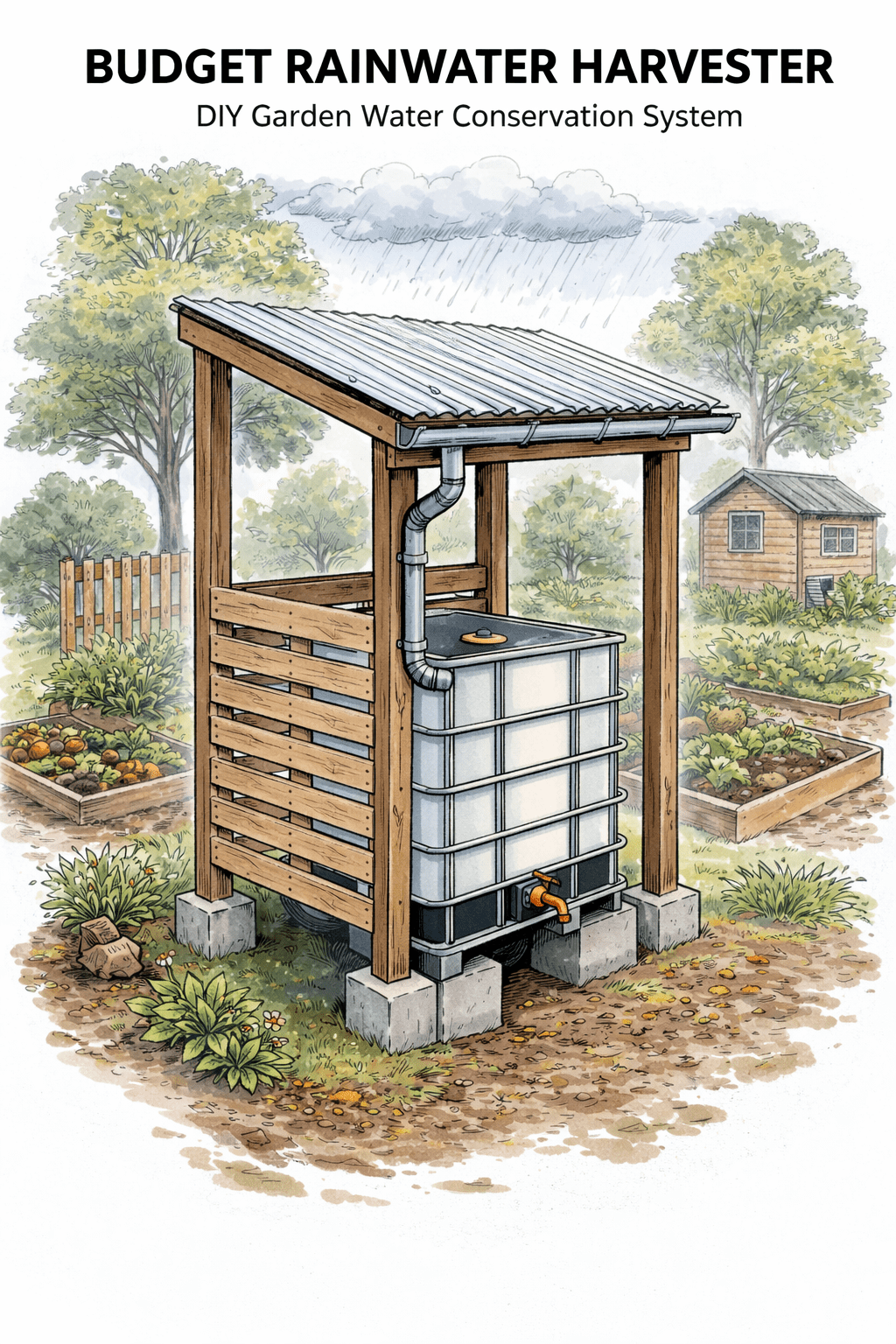

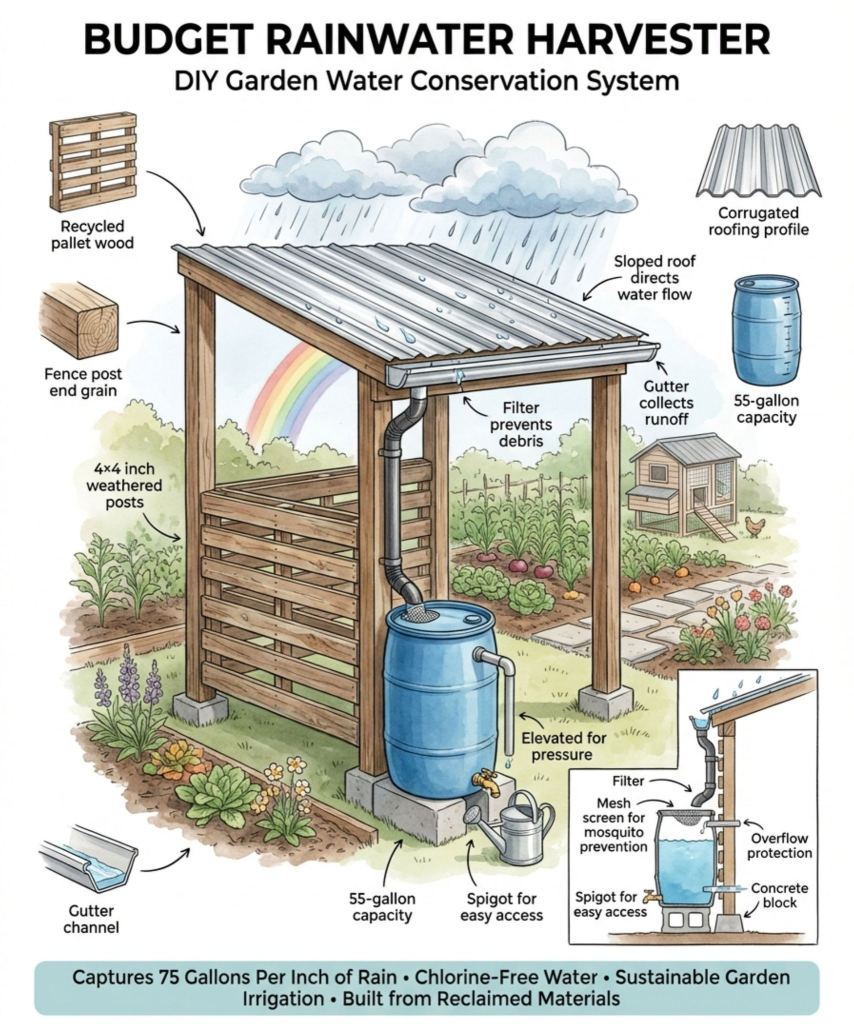

| The original image came from a Facebook page l follow called Garden Tips & Tricks. We are converting the pallet idea to hold an IBC. |

| The image that started this wasn’t mine. I came across it the way you come across most useful ideas these days — half-noticed, shared by someone working their own patch of ground, not selling anything, just quietly showing what they’d made. A simple timber frame, a sloping roof, a barrel underneath. Nothing new. Nothing clever. And yet it lingered. I recognised it immediately, not because of the design, but because of the thinking behind it. Someone looked at how much rain was falling and where it was going and decided to slow it down. To hold a little of it back. That impulse — to interrupt the rush — is something gardeners understand instinctively, even if we don’t always articulate it. Down on our own allotment, we’ve been talking more seriously this year about introducing water-harvesting stations. Not as a feature, and certainly not as a statement, but as a response to what’s already happening around us. The ground tells you before the headlines do. Winters are no longer gentle. They arrive heavy, persistent, and often overwhelming. Paths flood. Drains back up. Soil saturates and then sheds water like it’s had enough. And then, quietly, the seasons turn. A few dry weeks. A stretch of wind. Suddenly, we’re counting watering cans again. Rainwater harvesting sits right in that tension — between abundance and absence, often separated by only a short gap in time. Wet winters, fast water One assumption that still crops up in conversations about water conservation is that it’s primarily a summer concern. Droughts, hosepipe bans, stressed plants. That framing feels increasingly out of step with what we’re actually experiencing. UK winters are getting wetter, not just in volume but in intensity. Rain arrives in heavier bursts, over more extended periods, onto ground already complete. Water doesn’t soak in because it can’t. It runs, pools, floods, and disappears into systems never designed to hold it for later use. At the allotment, this is obvious. You can see where water wants to go. You can see which paths turn into channels and which beds slump under saturation. There’s no romance to it — just gravity doing what gravity does. The problem isn’t rainfall. It’s speed. When water moves too quickly, it’s effectively unavailable. It doesn’t recharge the soil properly. It doesn’t linger where roots can access it. It becomes a problem to be managed rather than a resource to be shared. Harvesting rain — even in modest, almost unspectacular ways — is one of the few tools we have to change that dynamic. Why shared systems matter On an allotment, the limitations of individual water storage become clear very quickly. A single butt beside a shed helps, but only up to a point. It fills fast in winter and empties just as fast in summer. It becomes personal, guarded, and occasionally resented. What interested us about the allotmenteer’s setup wasn’t the barrel. It was the station. The idea that water could be caught, stored, and accessed communally — not owned, not hidden, but simply there. That thinking naturally carries over to the Soil Hub as well. If soil is the shared foundation, then water is its bloodstream. It makes sense that access to both should be collective, visible, and grounded in the realities of the site. There’s also something important about removing the sense of individual scarcity. When water harvesting becomes a shared infrastructure rather than a personal stash, behaviour changes. People take what they need. They don’t over-apply. They become aware of levels, weather, and timing. It stops being about maximising extraction and starts being about working with what’s available. Rain is not neutral We talk about rain as if it’s uniform, but anyone who works outside knows better. Winter rain is cold, persistent, and often unwelcome. Summer rain is brief, warm, and almost celebratory. Plants respond differently. Soil responds differently. People do too. Harvested rain carries that seasonality with it. Water drawn from a barrel in April feels different from water drawn in August. Not scientifically different in a way that demands measurement, but different in how the garden receives it. One of the quieter observations from years of watering with stored rain is how gently it reintroduces moisture after dry spells. There’s no shock. No sudden collapse of dry structure. The soil seems to accept it more readily, as if recognising it. This is often explained away as nostalgia or bias, but there’s something real in it. Rainwater arrives without the chemical adjustments that make mains water safe for long pipes and human consumption—soil life notices. Containers notice. Greenhouse plants, especially, seem calmer for it. None of this makes rainwater harvesting a cure-all. It simply makes it appropriate. The myth of enough One of the most persistent myths around rainwater harvesting is the idea of “enough”. Enough barrels. Enough storage. Enough to get through summer without touching the tap. In practice, that threshold is rarely reached in small-scale systems. A few heavy watering sessions will empty even generous storage. This isn’t a failure — it’s a reality check. At the allotment, this honesty is helpful. You learn quickly that harvested water is best reserved for moments when it matters most: newly planted areas, propagation, containers, greenhouse use. You stop trying to replace mains water entirely and start using rain where it has the most significant impact. The Soil Hub will need to operate on the same principle. Harvesting stations won’t be there to guarantee supply. They’ll be there to soften demand, to bridge gaps, to reduce unnecessary pressure during peak periods. In a way, rainwater harvesting teaches restraint by design. You can’t forget how much you have, because you can see it. Soil still does the heavy lifting. It’s worth saying plainly: barrels don’t store most of the water that matters. Soil does. Healthy soil can hold extraordinary amounts of moisture, far more than any above-ground container. The difference between a bed that dries out in a week and one that holds through a dry spell is rarely rainfall alone — it’s structure, organic matter, biology. This is where water harvesting and soil care intersect rather than compete. Catching rain makes sense only if the soil beneath is able to slowly absorb it and retain it. At the allotment, winter saturation has made this painfully clear. Compacted paths shed water immediately. Beds that have been fed compost and left relatively undisturbed behave differently. They fill, drain, and retain in a rhythm that feels almost self-regulated. Harvested rain, applied thoughtfully, reinforces that rhythm. It doesn’t overwhelm. It tops up. Accepting excess Another assumption worth questioning is that all excess water is a problem. In increasingly wet winters, the instinct is to drain, channel, and remove. Sometimes that’s necessary — nobody wants standing water against structures or anaerobic soil everywhere. But there’s a difference between managing water and rejecting it outright. At both the allotment and the Soil Hub, part of the conversation now is about where water can safely linger, where slight wetness is acceptable, where overflow from harvesting stations should go — not into drains, but into planted areas that can cope. This kind of thinking requires a shift. It means seeing water not just as input, but as movement. Harvesting becomes one pause in a longer journey, not an endpoint. Practical limits, quietly acknowledged Shared harvesting systems bring their own challenges. Someone has to maintain filters. Overflow needs to be directed carefully. Barrels need secure bases, especially when full. In winter, freezing is a real consideration. These are not reasons to avoid the idea — they’re reasons to keep it grounded. The most successful systems are rarely the most elaborate. They’re the ones that are easy to understand, easy to maintain, and easy to adapt when conditions change. At the allotment, simplicity will matter more than capacity. At the Soil Hub, visibility will matter more than perfection. People need to see how the system works, not be impressed by it. Why does this feel timely? If this were just about sustainability messaging, I’d be less interested. But it isn’t. It’s about alignment — between rainfall patterns, soil health, shared spaces, and how we choose to respond. We’re entering a period where water is abundant and scarce almost at the same time. Wet winters, dry pressure, unpredictable transitions. Systems that rely on predictability struggle. Systems that allow for pause and adjustment cope better. Rainwater harvesting stations won’t solve this. But they will anchor us in it. They’ll remind us, each time we draw a can, that water has a history before it reaches our hands. A closing reflection That original image still sits in my mind, not because of how it looks, but because of what it assumes: that rain is worth catching, even briefly. That effort doesn’t have to scale to be meaningful. That working with water starts by noticing where it already wants to go. As we bring harvesting stations into the allotment and, eventually, into the Soil Hub, the intention isn’t efficiency. It’s attentiveness—a willingness to meet rainfall where it falls, rather than chasing it once it’s gone. In a country that is getting wetter and thirstier at the same time, that feels like a reasonable place to start. |

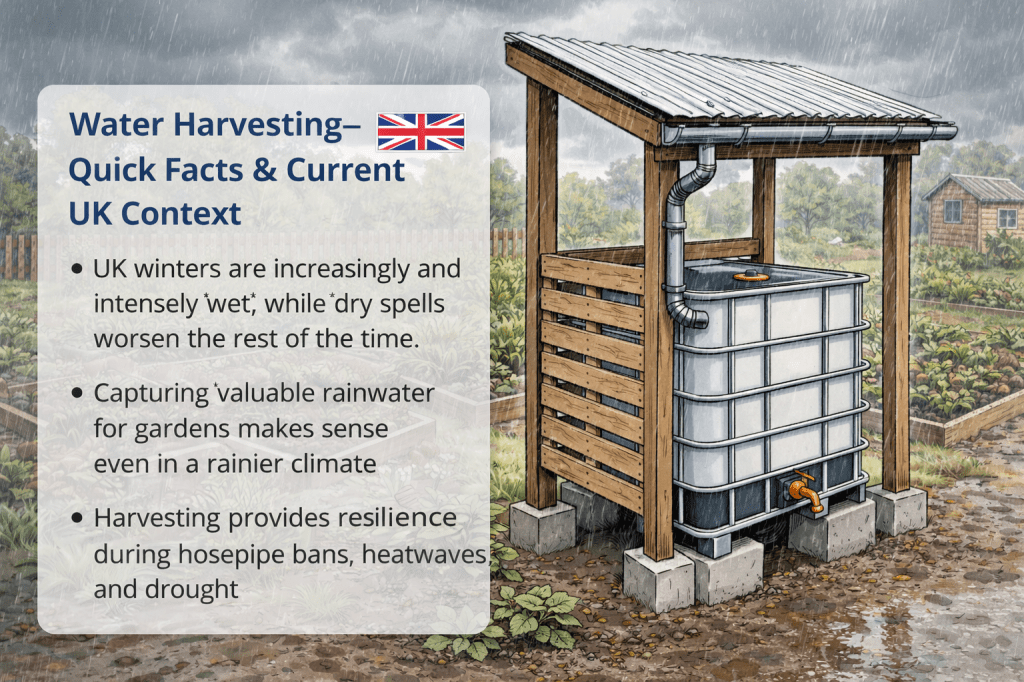

| Water Harvesting — Quick Facts & Current UK Context What Rainwater Harvesting Is Rainwater harvesting means catching rainfall where it lands — usually from roofs or other surfaces — and storing it for later use. In the UK, this typically feeds garden watering, greenhouses, ponds and other non-potable uses rather than the drinking water supply. (Wikipedia) Systems range from small water butts to larger tanks, such as 1000-litre IBC units or underground reservoirs, depending on need and scale. (Wikipedia) Why It Makes Sense (Even in a Wet Climate) The UK is often thought of as uniformly rainy — but rainfall is seasonally uneven, with very wet winters and increasingly dry summers, and both extremes are becoming more frequent due to climate change. (The Guardian) Harvesting captures water during wet phases so it can be used when the land dries out—an efficient strategy for gardens, allotments and community soil hubs. How It Helps Gardens & Shared Spaces Stored rainwater can reduce reliance on the mains supply for irrigation, especially during hosepipe bans. (Countryfile) At allotments and hubs, community harvesting systems, such as shared IBC tanks, can provide visible, equitably accessible supply points for all growers. Using rainwater for plants supports soil biology and plant health without the temperature and chemical differences of mains water. UK Water Realities (Recent News) The Guardian UKGBC Water Magazine Countryfile The Guardian GOV.UK Here’s what’s been in the news: Intense UK rainfall and flooding: Storm systems like Storm Chandra have brought record wet conditions and flooding, underscoring how extreme precipitation events are increasing — with impacts on wildlife and soil systems alike. (The Guardian) Drought is still relevant: Despite wet spells, UK regions continue to experience below-normal river flows and drought indicators, meaning water availability remains stressed. (Water Magazine) Drought planning and warnings: Government drought groups have met to discuss national water shortfalls and response strategies, reflecting both dry periods and the need for long-term resilience.(GOV.UK) Gardening guidance includes rainwater harvesting: Practical advice for gardeners in mainstream outlets now lists rainwater harvesting as a key water-efficiency approach alongside species selection and watering timing. (Countryfile) Longer-term pressures on water supply: Reports note that water shortages — historically associated with southern summers — are part of larger structural concerns about water availability in England. (UKGBC) Public discussion on water scarcity: Debates about UK water stress, conservation, and public behaviour have entered mainstream news, challenging assumptions that a wet climate alone secures supply. (The Guardian) Practical Benefits for Community Growing Reduces mains pressure: Captured rainwater eases demand on mains systems, particularly in the peak growing season. Buffers climate variability: By storing rainfall from winter and rainy spells, shared systems help gardens through intermittent dry periods. Encourages efficient use: Visible storage makes people more aware of water as a resource — not an unlimited one. Things to Keep in Mind Harvesting complements but doesn’t replace mains water — especially for drinking, hygiene, or full plot irrigation in dry spells. Storage capacity and catchment area limit how much water can be held; design must match your soil hub’s needs. UK rainfall patterns are shifting: wetter winters don’t automatically alleviate summer water stress, so buffering with storage still matters. |

| About our writing & imagery Most articles reflect our real gardening experience and reflection. Some use AI in drafting or research, but never for voice or authority. Featured images may show our photos, original AI-generated visuals, or, where stated, credited images shared by others. All content is shaped and edited by Earthly Comforts, expressing our own views. |