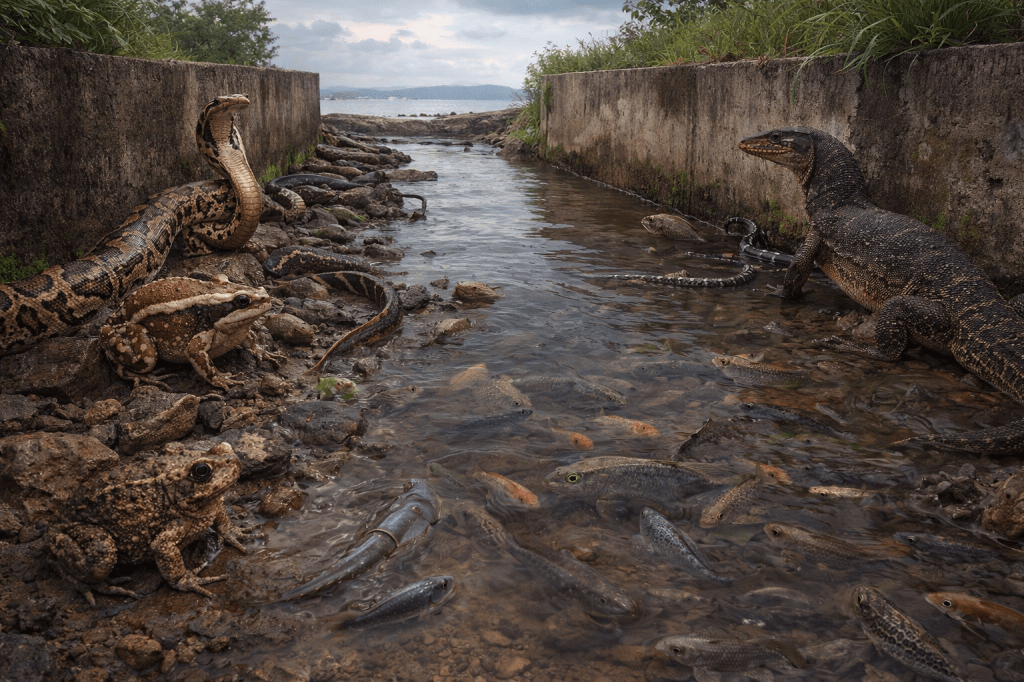

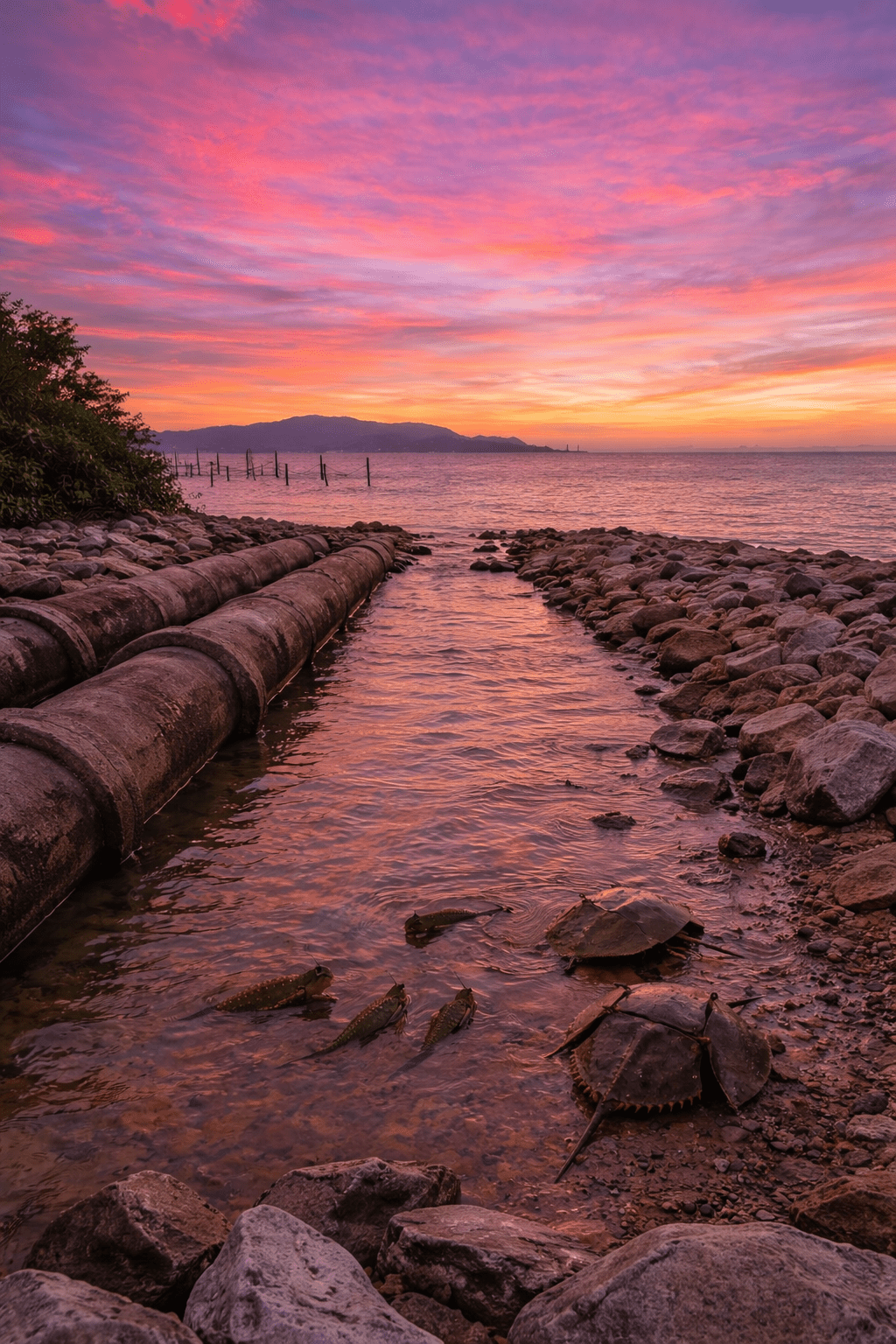

| I was told, as a child, not to go into the monsoon drains. The warning was never dramatic. It was spoken as fact. Everyone understood that when the rains came, the land changed its rules. The water rose quickly. Concrete became slick. Creatures moved that were not always visible at other times. The drains were not places for carelessness. I was there because my father was stationed at RAAF Base Butterworth in Malaysia. We lived where service families lived, close to the base, close to local communities, and close to land that had not yet been sealed or separated. It wasn’t a choice made by a child, only a condition of life — one that placed me, without ceremony, inside a landscape that was still functioning in ways I would only understand much later. And yet, like many children, I did go into the drains. Sometimes alone. Sometimes with local lads from nearby kampungs. Sometimes with friends from school. It wasn’t reckless. It was ordinary. We learned where the footing held and where it didn’t, how the water behaved after heavy rain, and how stillness often mattered more than speed. We learned by watching first, by moving slowly, and by paying attention. In the late 1960s, the area where we lived was not dense. Houses existed within space rather than replacing it. Beyond them were palms, scrub, rubber trees, secondary jungle, and long edges where human order loosened, and the land resumed its own conversation. Water did not disappear underground. It travelled openly, following gravity and habit, along concrete channels that ran beside roads and gardens and continued outward. Those drains did not end abruptly. They ran all the way to the sea. They emptied into the strait between Butterworth and Penang, and that mattered. It meant everything upstream was connected to tide and salt, to mangrove and mudflat, to a larger body that breathed in and out twice a day. Fresh water carried stories downhill. The sea answered in return. During the monsoon, the drains became something else entirely. They filled. They connected. They began to move. What I remember most clearly is that there was always something in them. After the rain, frogs appeared first. Not timidly, but as if they had been waiting. Some sat heavily in the shallows, unbothered by observation. Others clung to walls and vegetation, pale and patterned against concrete darkened by water. At night, their calls layered the air — not a single sound, but many, overlapping and responding, rising and falling with humidity. They were not rare. They were not remarkable. They were simply present. That presence carried meaning, even before I had words for it. Amphibians are exacting. They do not tolerate indifference from their surroundings. Where they gather in number, water is clean enough, still enough, connected enough. The land is still answering itself honestly. Fish followed the water. They appeared where there had been none the day before, making the movement of rain visible. Some lay still at the bottom, sensed more than seen. Others hovered just below the surface, rising occasionally for air when the water thinned. In calmer sections, softened by leaves and debris, slower fish moved with deliberate ease. As the drains widened and slowed toward their mouths, life thickened. Where fresh water met salt, everything seemed to gather. The drain outlets were busy places — fish schooling in shifting light, larger bodies moving through the shallows, crabs sidling at the edges, birds waiting for opportunity. The tide pulled one way, the rain pushed another, and life occupied the tension between them. To a child, it felt endlessly interesting. To the land, it was simply a function. The monsoon erased boundaries temporarily. Drains joined ditches. Ditches joined streams. Streams carried everything outward to the mangrove and sea. Life moved laterally rather than hierarchically, following opportunity rather than permission. Predators came not as intrusions, but as consequences. Snakes used the drains as shelter and passage. They were not aggressive, not theatrical, simply present — moving with purpose rather than threat. Some were seen clearly; others were sensed only by stillness or the sudden absence of sound. On occasion, something much larger passed through, its size registering not as fear but as scale—a reminder that the system extended beyond what could be seen at once. Monitor lizards patrolled the edges, ancient and practical, uninterested in our ideas of wild and domestic. They belonged to the place in a way roads never quite did. This was not wilderness in the romantic sense. It was a working ecology. Human settlement and animal life overlapped without ceremony. The drains were not failures of planning; they were expressions of it — places where water was allowed to behave like water, and life responded accordingly. The adults were right to warn us. These systems demanded respect. Water could rise suddenly. Algae made concrete treacherous. Creatures sheltered where shelter existed. The danger lay not in emptiness, but in richness. What I learned, without being taught, was attentiveness. You could be cautious without being fearful. You could step in without blundering. You could learn simply by watching long enough, by moving at the pace the place required. That way of seeing settled quietly and stayed. I did not grow up wanting to control nature or curate it. I grew up understanding that life gathers where conditions allow it to and withdraws when those conditions are removed. I learned that edges matter — especially where fresh water meets salt, where land loosens its grip, and systems overlap. I learned that overlooked places often hold the deepest complexity. Only later did I recognise the other lesson present there: impermanence. Those drains still exist in name, but not in spirit. They are sealed, narrowed, and accelerated. Water moves quickly now, stripped of its pauses. Frogs are fewer. Fish appear briefly, if at all. The mouths that once teemed with exchange are quieter. Children are warned away not because the drains are alive, but because they are empty in a different, more dangerous way. What was lost was not only species but also relationships. I return to these memories not out of nostalgia, but out of grounding. They remind me what a functioning system looks like when it is allowed to exist quietly alongside people. Not pristine. Not controlled. Simply coherent. That kind of childhood does not provide answers. It provides orientation. It teaches you to look down as well as outward. To notice what lives close to the ground and where waters meet. To understand that care begins with attention, and attention begins with stillness. The monsoon drains were never meant to teach philosophy. They were simply places where water was allowed to move — from land to sea — and life was allowed to respond. Once you have grown up inside that truth, even briefly, you spend the rest of your life recognising when it is missing — and quietly trying to make room for it again. |

| Fact box: Life commonly seen in the monsoon drains Frogs and toads Found throughout the drain system, especially after rain, forming the base of the food web. Malaysian Painted Frog Robust, ground-dwelling frogs thriving in temporary water. Asian Common Toad Highly adaptable, often moving calmly along drain edges. Four-lined Tree Frog Agile and vocal, clinging to walls and vegetation at night. Fish (freshwater to brackish) Moving freely with rain and tide, especially abundant near drain mouths. Catfish Bottom-dwellers tolerant of low oxygen. Snakeheads Air-breathing predators suited to shallow, fluctuating water. Gouramis Slower fish favouring calmer, vegetated sections. Tilapia and guppies Introduced species thriving in warm, nutrient-rich conditions. Snakes Using drains as corridors rather than confrontation zones. Cobras Often moving calmly through drain systems. Kraits Secretive and easily overlooked. Brown snakes and water snakes Well adapted to wet ground and transitions. Large reptiles Reticulated python Occasional passage species, moving through connected habitat. Monitor lizard Opportunistic and intelligent, present where systems were intact. |

Unless stated, featured images are my own work, created independently or with the assistance of AI.

You had an interesting childhood, Rory. I was a curious child, and loved exploring wooded areas, and such. Though places, I wouldn’t want to visit today.

LikeLike

This portrays a very interesting scenario. The image though is quite scary

LikeLiked by 1 person